OAK ISLAND

BLACKSMITHING

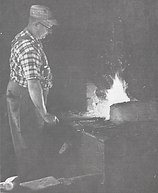

As a young boy, I grew up in Blue Mountain, N.S., a rural inland community. A family relative in this community, Clifford Legge, was a working blacksmith. Many times, I visited him with my family. I watched in wonder at the sparks, the forming of metal, and the many shoeings. Nearby in another community, New Ross, was another blacksmith equally respected by the family, which I often visited with my family, too. As a boy of ten, I remember this blacksmith, Jack Morley, telling me that if I could lift the anvil sitting in the corner of the table, I could have a dollar. A dollar! That could buy me a lot of chocolate bars. I took a mighty strain on the anvil. It didn’t budge. No dollar. I remarked it was bolted down. “No, no”, he said, “see…”, and he promptly lifted it. Very strong and adept, he was in his movements as he blacksmithed and shod oxen. I took notice…somewhat. How could I know that someday I would be working as a traditional blacksmith in his very shop! And indirectly taught by the very blacksmith that was a family relative.

Let me explain. I always had a ‘knack’ for crafting, and spent much time as an early adult learning and practicing traditional skills including woodworking, leatherworking, and especially metalworking which included studying and identifying countless iron artifacts. I adored elders who were like-minded, especially those who were willing to teach me. After a stint in the forestry industry, I was employed as an ox teamster/herdsman at the Ross Farm Museum site in New Ross, wherein Jack’s shop was now located. My lunch break was a half hour longer than many of the others. I would ‘wolf-down’ my lunch, and wander down to the blacksmith shop to watch, then blacksmith, Roy Levy, perform amazing feats of metal manipulation. Occasionally, I would ask him to show me how a procedure was accomplished. He was, and is, a forthright personality ‘suffering no fools’, but he readily became a great instructor teaching me what to do. Maybe he saw a pupil worthy of his administrations. My blacksmithing knowledge ascended exponentially, surmising approximately one third of my eventual career skill and knowledge. Roy was nearing retirement, and I assumed blacksmith duties after he left. I wished I had more time with Roy, however, another blacksmith, Stephen Workman, who worked there previous to Roy, continued to teach me a few other aspects of traditional blacksmithing, especially what not to do, particularly when shoeing oxen. This blacksmith was himself taught by the very family relative I mentioned earlier, Clifford Legge. So, I considered myself partially taught, through Stephen, by Clifford. Stephen, along with several others, over the next year or two, taught me another, surmised, one third of my know-how. Finally, the last surmised third of my expertise was gained by myself. Many times, numerous museums and historical entities would request reproductions pieces made; for example, door latches in the French style of the 1650s, or hinges in the English style of the 1820s. This sparked a renewed yearning for related erudition. Countless hours of research concerning French, English, and German styles of artifacts from the 1600s onward ensued.

Clifford Legge

The Morley Blacksmith Shop

Jack Morley

Roy Levy